library(kableExtra) # for tables

options(kableExtra.html.bsTable = T)

library(tidyverse) # for data wrangling

library(knitr) # for changing options when knitting

library(ggplot2) # for plotting11 Introduction to Bayesian statistics

Learning objectives

Understand differences in how probability is defined in frequentest and Bayesian statistics.

Understand how to estimate parameters and their uncertainty using Bayesian methods.

Compare Bayesian and frequentest inference, starting with a simple problem where we can solve for the Bayesian posterior distribution analytically.

As an aside, you may be surprised to learn that there are multiple ways to define probability. In fact, there are many, many more ways than two; philosophers and mathematicians have long debated the definition and meaning of probability (for an interesting discussion, see: Lyon 2010).

11.1 R packages

We begin by loading a few packages upfront:

In addition, we will use functions from the rgl package (Murdoch and Adler 2021) for creating a 3-D plot that can be interacted with in the html version of the book.

11.2 Review of frequentist statistics

In frequentist statistics, we define probability in terms of the relative frequency of some event across an infinite sequence of random, repeatable experiments or random trials. This definition of probability is central to key concepts in frequentist statistics:

a sampling distribution describes the distribution of parameter estimates across repeated events (where an event is represented by the process of collecting and analyzing data using the same methods each time).

a null distribution is the distribution of parameter estimates across repeated events in the special situation where the null hypothesis is true.

a confidence interval is an interval that should capture the true unknown parameter for a specified proportion of all events (where now, the event also includes calculating the confidence interval from the sample data).

a p-value is the chance of obtaining a sample statistic as extreme (or more extreme than) an observed sample statistic, if the null hypothesis is true. Again, we consider repeated events of collecting data and calculating the same sample statistic under a situation where the null hypothesis is true.

In frequentist statistics,

- Parameters are generally assumed to be fixed quantities that are unknown.

- Data are random and used to estimate parameters (e.g., using Maximum Likelihood).

- Data are used to test hypotheses which are either TRUE or FALSE.

The goal is to make ‘good’ decisions with high probability (across potential repeated experiments).

11.3 Bayesian statistics

Bayesians also aim to make good decisions with a high probability, but as we will see, probability represents something a little different when it comes to assessing uncertainty in estimation and inference. Specifically, for Bayesians, probability refers to one’s belief given observed data and any prior assumptions about unknown parameters. Although some have criticized Bayesian statistics on the grounds that it is subjective, it is important to stress that Bayesian analyses result in informed beliefs (i.e., informed by data), and in most cases, Bayesian and frequentist analyses will result in similar inferences. Furthermore, although prior beliefs can sometimes make a difference, they are less influential with large data sets.

In Bayesian statistics, all parameters are unknown and their uncertainty is represented by probability distributions (prior distributions before any data are collected and posterior distributions after data have been collected and analyzed).

In Bayesian statistics:

- Random variables are used to model all sources of uncertainty. Because parameters are uncertain, they will have a distribution!

- Data are treated as fixed and inference is performed conditional on the data.

- Prior assumptions are combined with a likelihood, leading to a posterior distribution that describes one’s beliefs about parameters and hypotheses, conditional on the observed data.

Whereas a frequentist will tell you that hypotheses are either true or false (with probability = 1), Bayesians are comfortable quantifying P(Hypothesis | data), which will range between 0 to 1. Bayesians report credible intervals (similar to confidence intervals). These constructs are similar, but Bayesians can and will refer to the probability that a parameter is in a confidence interval, whereas frequentists will insist that the parameter is in the interval or not (i.e., the probability is 0 or 1).

11.4 Comparing frequentist and Bayesian inference for a simple model

Let’s compare Bayesian and frequentist inference using a simple example. Suppose we are interested in estimating the probability,

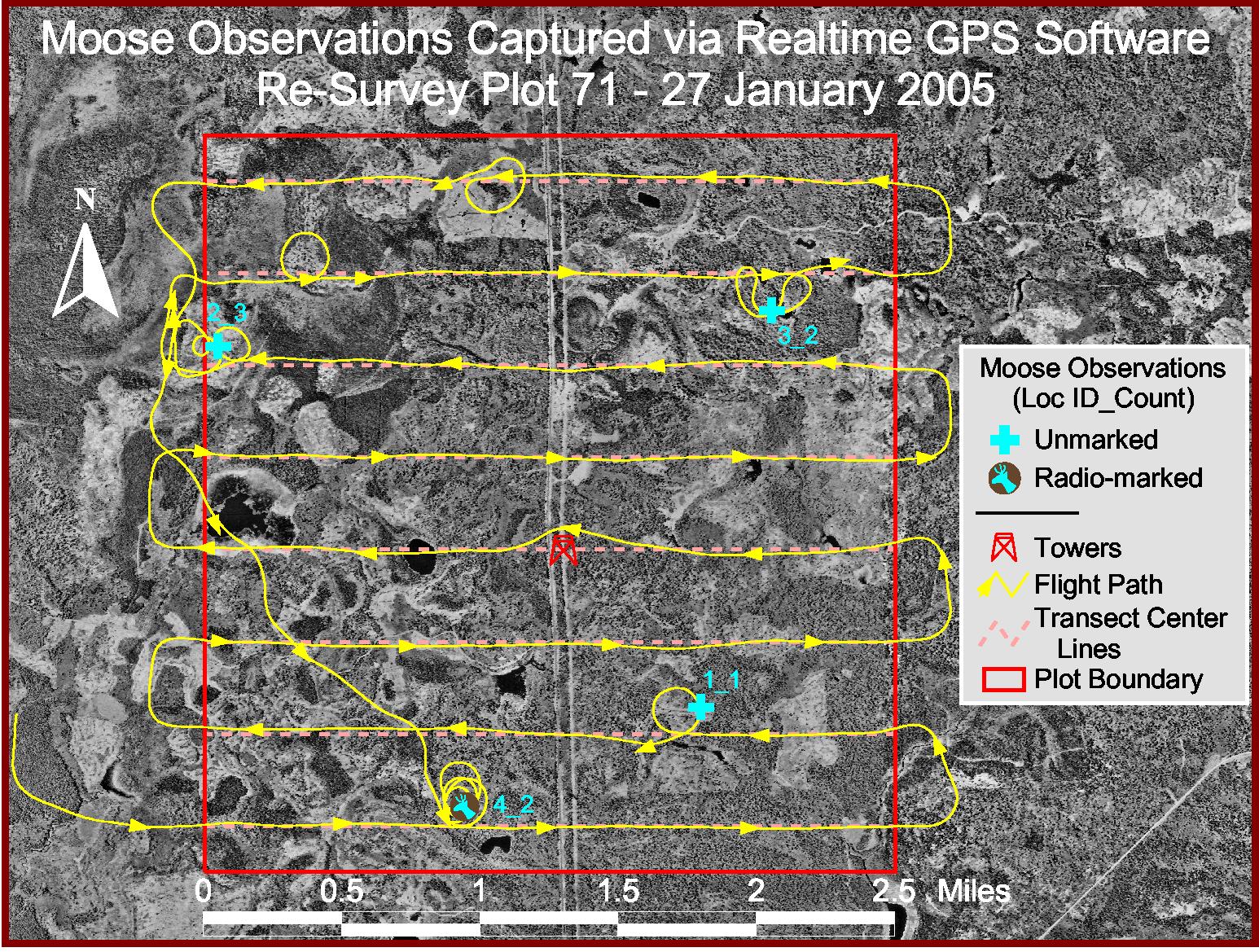

From 2004-2007, the MN DNR conducted a series of detection trials using radiocollared moose to estimate

The probability of detecting a moose will depend on where the moose is located (e.g., the amount of cover that shields the moose from view, termed visual obstruction). We will eventually consider ways to model the probability of detection as a function of the amount of visual obstruction (Chapter 16). For now, however, we will assume that the probability of detection is constant and that all detection trials are mutually independent.

11.4.1 Maximum likelihood

If each trial is independent with constant probability of detection, then we can represent the data-generating process as a Binomial random variable:

The likelihood is thus given by:

To use Maximum Likelihood, we consider the likelihood as a function of

Solving for

We could calculate the variance directly using the result that:

Alternatively, we could use the asymptotic results from the section on maximum likelihood (Section 10.6) to derive an expression for

When our sample size,

Think-Pair-Share: Where does this expression come from?

In the section on maximum likelihood estimators (Section 10.6), we learned that for large

Lastly, we approximate

Let’s calculate the large sample, Normal-based confidence interval in R for our moose data:

# Estimate and SE

y <- 54

n <- 124

(p.hat <- y/n) [1] 0.4354839(se.p.hat <- sqrt(p.hat*(1 - p.hat)/124))[1] 0.04452597# Confidence Interval

round(rep(p.hat, 2)+ c(-1.96, 1.96)*se.p.hat, 2)[1] 0.35 0.52Thus, our 95% confidence interval for

11.4.2 Aside: how well do these frequentist intervals work

The above confidence interval is based on a large-sample Normal approximation for maximum likelihood estimators. You may have learned in an introductory statistics class that these intervals work well only when

We can use simulation to explore how well these intervals perform. Specifically, we will:

- Simulate 10,000 binomial random variables using:

x <- rbinom(10,000, size = n, p)with a range of values forpandn. - Generate 10,000 estimates of

x/n). - Generate 10,000 95% CIs for

- Determine how many of these CIs include the true

# Create empty object to collect data

simulCIs = data.frame()

# Loop over values of p and n

for (n in seq(5, 200, 1)) {

for (p in seq(.05, .95, .05)) {

# Simulate "moose detections" (i.e. how many moose you see in the n trials)

ys <- rbinom(10000, size = n, prob = p)

p.hats <- ys/n

se.p.hats <- sqrt(p.hats*(1-p.hats)/n)

# Calculate 95% confidence intervals

up.CIs <- p.hats+1.96*se.p.hats

low.CIs <- p.hats-1.96*se.p.hats

# Determine the percentage of confidence intervals that contain p

perc.in.CI <- sum(I(low.CIs < p & up.CIs > p))/10000

# Save n, p, and % of CI containing p into the dataframe

simulCIs <- rbind(simulCIs,c(n,p,perc.in.CI))

}

}

#name the columns in the simulation data

names(simulCIs) <- c("n", "p", "perc.in.CI")We will use the plot3d function in the rgl library (Murdoch and Adler 2021) to create a 3-D scatterplot of the results, below (if you are viewing the html version of the book, you should be able to rotate this plot):

We see that the confidence intervals perform well (close to 95% of the intervals contain the true

11.4.3 Bayesian inference for

Let’s see how Bayesian Inference might differ. Here are the steps involved:

- Specify a likelihood for the data,

- Specify a prior distribution for the parameters,

- Use Bayes rule (Equation 11.1) to determine the posterior distribution of

The posterior distribution,

In Equation 11.1,

Let’s now work through these three steps when analyzing the moose detection data.

- Specify a likelihood for the data – we can again use the binomial likelihood:

- Specify a prior distribution for

- a uniform distribution on the (0, 1) interval

- a beta distribution, since it is the only distribution we have learned about with support on the (0, 1) interval.

The beta distribution has two parameters,

Recall from Chapter 9,

The beta distribution can take on a number of different shapes depending on the values of curve(dbeta(x, 1, 1), from = 0, to = 1)).

Let’s use a

Rather than write down the full equation for the posterior distribution, including the integral in the denominator, we will use a common trick that works when we have what is called a conjugate prior. A conjugate prior is one that results in a posterior distribution that is from the same family as the prior distribution (in this case, we will see that the posterior distribution is again a beta distribution). To see how this works, we begin by writing down an expression that is proportional to the posterior distribution:

You may or may not immediately recognize that this expression is proportional to a beta distribution with parameters (

The constant,

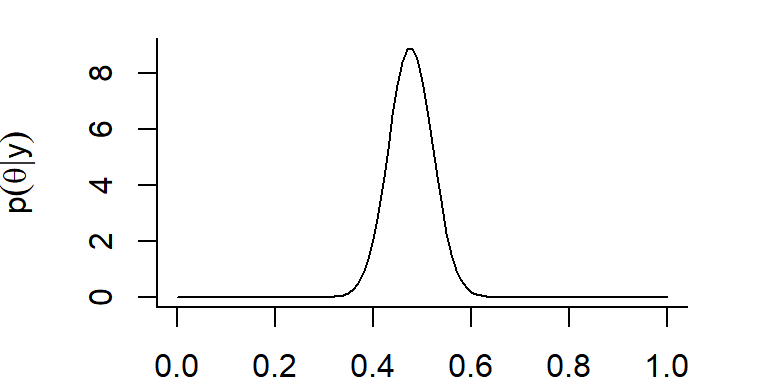

Let’s use curve to plot the posterior distribution = beta(60, 66):

par(bty = "L", mar=c(2, 4.1, 1, 2.1))

# Plot the Posterior Distribution of theta

plot(curve(dbeta(x, shape1 = 60, shape2 = 66), from = 0, to = 1),

type = "l",

xlab = expression(theta),

ylab = c(expression(p(group("", theta, "|") * y))))We can use this posterior distribution to form a 95% credible interval. To do so, we need to find the endpoints,

Think-Pair-Share: What function in R can we use to calculate these endpoints?

Remember, we can find quantiles of a distribution using q* (in this case, qbeta):

# 95% credible interval

round(qbeta(c(0.025, 0.975), shape1 = 60, shape2 = 66), 2)[1] 0.39 0.56We get the exact same endpoints as our frequentist confidence interval! Only now, we are free to say that the probability that

11.4.4 Comparing Interpretations: frequentist vs. Bayesian

For this simple problem, we found that our intervals were identical:

- frequentist 95% confidence interval for

- Bayesian 95% credible interval for

With the Bayesian interval, we can say that the probability that

For many readers, the interpretation of the Bayesian interval will seem more natural and this often adds to the appeal of Bayesian methods2. Nonetheless, it is still important to consider the performance of Bayesian methods across repeated experiments. For example, we might use simulations to determine if Bayesian 95% credible intervals contain fixed parameters used to simulate data 95% of the time, what statistician Robert Little refers to as calibrated Bayes (Little 2006).

Often we will find that Bayesian and frequentist methods will lead to a similar conclusions. So, it is helpful to ask, why or when should you prefer to use Bayesian methods? Dorazio (2016) suggests Bayesian inference is most useful in the case of:

- Hierarchical models of data that “link a submodel of sampling processes with a submodel of ecological processes.”

- Inference for latent (i.e., unobserved) state variables

- Missing data problems

- Intractable likelihood functions

- Complex models of different sources and types of data (with shared parameters); this is currently a hot topic in ecology where integrated population models (Schaub and Kéry 2021) and integrated species distribution models (Isaac et al. 2020) are frequently used to combine several sources of data when estimating demographic parameters and species distributions, respectively.

In addition, some of you may prefer Bayesian methods in general because:

- It is relatively easy to characterize uncertainty for functions of model parameters (no need for the bootstrap or delta method).

- The interpretation of credible intervals is appealing.

- Bayesian statistics is philosophically appealing since all inferences come from the posterior distribution. There is no need for separate theories for estimation, hypothesis testing, multiple comparisons, etc.

On the other hand, some concerns that arise when using Bayesian statistics include:

- With small samples, priors can make a big difference, and therefore, Bayesian methods can be criticized from a standpoint of perceived subjectivity. Furthermore, there are situations where even “vague” priors can end up having a significant influence on the results of an analysis (e.g., Lele 2020.).

- MCMC methods for estimating parameters can be computationally demanding and difficult to implement reliably (though software like JAGS (Plummer et al. 2003) and STAN (Carpenter et al. 2017) help).

These days, many applied statisticians (including me) will use a combination of Bayesian and frequentist methods. Yet, this has not always been the case, and there are still some statistical ecologists that feel strongly that Bayesian methods should not be generally adopted (see e.g., Lele and Dennis 2009). For example, consider the quote from Dennis (1996) (p. 1095-1103), below:

Ecologists should be aware that Bayesian methods constitute a radically different way of doing science. Bayesian statistics is not just another tool to be added into ecologists’ repertoire of statistical methods. Instead, Bayesians categorically reject various tenets of statistics and the scientific method that are currently widely accepted in ecology and other sciences. The Bayesian approach has split the statistics world into warring factions (ecologists’ “density independence” vs “density dependence” debates of the 1950s pale by comparison), and it is fair to say that the Bayesian approach is growing rapidly in influence

11.5 References

It is difficult to give a precise yet easily digested definition for closed form solution. I like the definition given at https://www.statisticshowto.com/closed-form-solution/, which suggests that the solution should only include: 1) a finite number of symbols, only

The same can be said for conclusions from hypothesis tests. Contrast these two conclusions: a) If