library(dplyr) # for data wrangling

library(knitr) # for options when knitting

library(ggplot2) # for plotting

theme_set(theme_bw()) # black and white background

library(ggthemes) # for colorblind palette12 A Brief introduction to MCMC sampling and JAGS

Learning objectives

Gain insights into how Markov chain Monte Carol (MCMC) sampling works.

Be able to implement your first Bayesian model using Just Another Gibbs Sampler (JAGS) software.

12.1 R packages

We begin by loading a few packages upfront:

In addition, we will use data and functions from the following packages:

R2jagspackage (Su and Masanao Yajima 2021) for calling JAGS from Rmcmcplots(Curtis 2018) andMCMCvis(Youngflesh 2018) packages to help with visualizing MCMC results

12.2 Introduction to MCMC sampling

In our moose detection example from Chapter 11, we could determine the posterior distribution analytically. Usually, we will not be so lucky. In particular, in most cases, there will be no closed form solution to:

Instead, we will generate samples that we can use to summarize the posterior distribution,

12.3 Metropolis algorithm

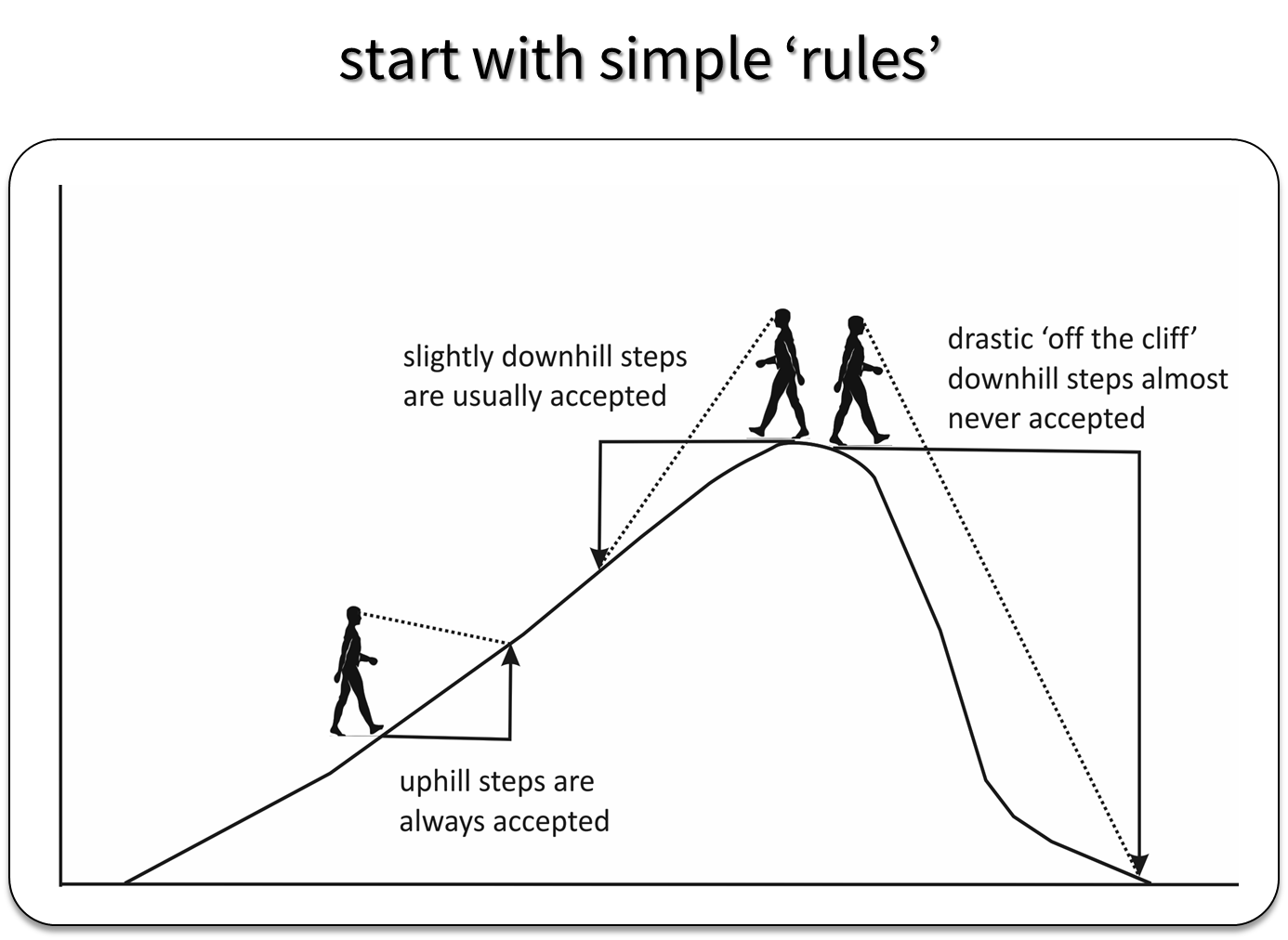

MCMC approaches generate a sequence of parameter values using a set of rules that allow the sampler to explore the full range of support of the posterior distribution, while spending most of the time in areas where the posterior distribution is at its highest point (Figure 12.1).

Remember, the posterior distribution is given by:

Consider two possible values of

The Metropolis algorithm uses this relative likelihood to determine a sequence of parameter values using the following algorithm:

Initiate the Markov chain with an initial starting value,

Generate a new, proposed value of

rnorm(mean =)).Decide whether to accept or reject

If

If

Return to step 2, replacing

Note that step 3 ensures that the proposed parameter values that move us up the probability hill (towards higher values of the posterior distribution) are always accepted, but also that we do not get stuck at the top of the hill (i.e., we continue to sample from the full range of parameters supported by the posterior distribution). This strategy is not too difficult to program - if you want to see what R code would look like for a Metropolis sampler, see: https://theoreticalecology.wordpress.com/2010/09/17/metropolis-hastings-mcmc-in-r/.

We will continue to sample until:

The distribution of

The MCMC sample,

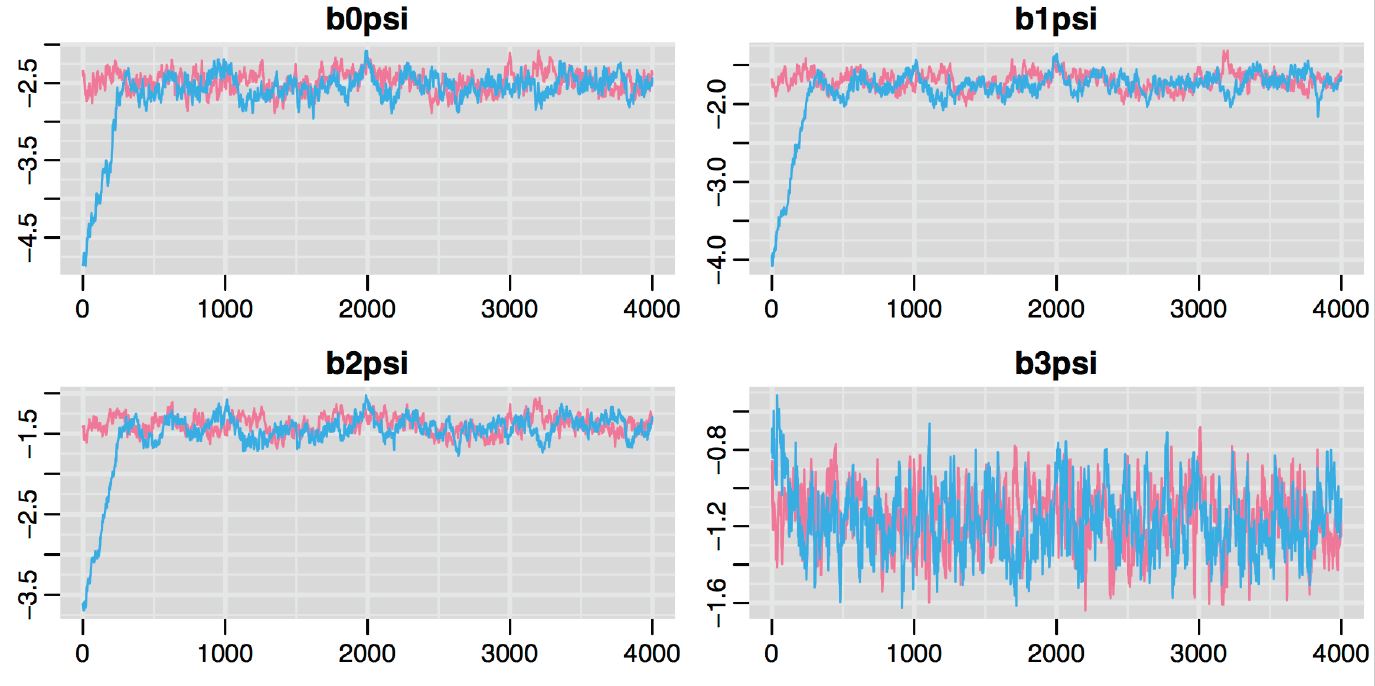

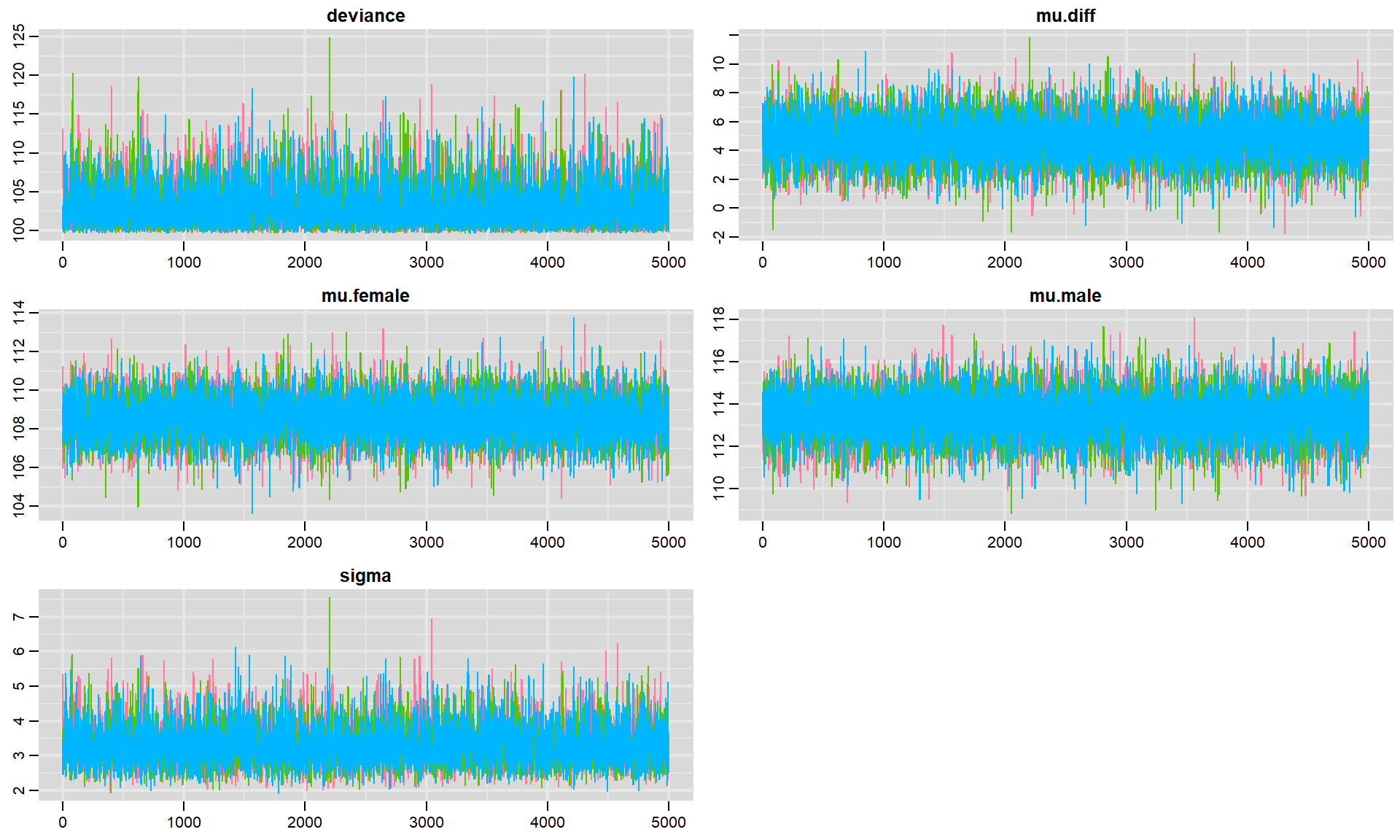

An example Markov Chain may look something like Figure 12.2. This plot is called a traceplot, and it depicts the series of parameter values generated using MCMC sampling for 4 different parameters (represented in the different panels of the plot). In this case, two different Markov chains (shown in red and blue) were initiated at different starting values. Eventually, the two chains converge in distribution as evidenced by the red and blue plots largely overlapping after the first set of 500-1000 samples. Usually, we will discard the initial parameter values where the chains are clearly sampling different regions of the parameter space, which we label as a “burn-in” period. Once we have these samples, we can estimate

How do we know if we have sampled long enough - i.e., that our sample has converged in distribution to

- Run multiple chains (starting in different places) and see if they converge on similar distributions

- Discard the first

- Consider the Gelman-Rubin Statistic (Gelman, Rubin, et al. 1992), Rhat, which is output by JAGS. Rhat compares the variance of parameter values between chains to the variance of parameter values within chains. Values near 1 suggest likely convergence. As a general rule, Rhat should be less than 1.1.

12.4 Aside: Sampler performance

With Metropolis or Metropolis-Hastings (the latter allows for non-symmetric proposal distributions), we need to consider how to generate good proposals for our parameters (i.e., “candidate” parameter values during step 2 of the process). This may require setting one or more “tuning” parameters to ensure the sampler does not get stuck at the top of the hill or jump too far away from the current value that we miss the hill altogether. For example, when using the normal distribution, we can try different values of

In this book, we will be using JAGS (Plummer et al. 2003) to implement Bayesian models. There are a number of packages available to run JAGS from within R (e.g., rjags , runjags, R2jags, rube, etc); we will generally use R2Jags (Su and Masanao Yajima 2021). JAGS has a variety of different MCMC algorithms at its disposal, and it will attempt to determine the best algorithm depending on the likelihood and set of prior distributions (one for each parameter) that we give it. Although JAGS is quite powerful, there are other samplers developed in recent years that are not available in JAGS but are more efficient (i.e., they converge in distribution quicker and their samples are less autocorrelated). For example, STAN (Carpenter et al. 2017), a popular alternative to JAGS, employs a “No-U-Turn” (NUTS) sampler that is typically more efficient at sampling the posterior distribution (Hoffman and Gelman 2014); for a visual demonstration of different samplers, see http://elevanth.org/blog/2017/11/28/build-a-better-markov-chain/. STAN can also be run from R (Stan Development Team 2019), but the syntax is a little more challenging to learn.

12.5 Specifying a model in JAGS

To run a model using JAGS, we will need to:

- Specify prior distributions for all model parameters.

- Specify the likelihood of the data.

- Fit the model by calling JAGS from R to generate samples using its built in MCMC routines.

- Evaluate whether or not we think the samples have converged in distribution to

- Use our samples to characterize the posterior distribution,

Let’s revisit our linear model for comparing the mean jaw lengths of male and female golden jackals from Section 3.6.1. The data are again provided, below:

males<-c(120, 107, 110, 116, 114, 111, 113, 117, 114, 112)

females<-c(110, 111, 107, 108, 110, 105, 107, 106, 111, 111)As before, we will assume the mean jaw lengths for males and females are normally distributed, with sex-specific means,

This model has 3 parameters:

We want to choose priors that are “dispersed” (meaning they allow for a wide range of possible values). One way to do this is to use Normal distributions with large variance parameters (small precision parameters). Alternatively, we can use uniform distributions that allow for a wide range of values. We will use a mix of these strategies, below:

Priors:

JAGS code (see jaw.mod below) looks just like R code, but with some differences:

- JAGS code is not executed (it just defines the model)

- It does not matter how we order our code (we can define the prior before likelihood or the likelihood after prior - it will not make a difference).

There are 6 types of objects in JAGS:

Modeled data specified using a

Unmodeled data: these are objects that are not assigned probability distributions. Examples of unmodeled data include predictors, constants, and index variables used in loops.

Fixed-effects parameters: these are parameters that are assigned uninformative priors.

Random-effect parameters: these are parameters associated with different groups that are linked together by a common prior distribution. This common prior distribution will include additional parameters called hyperparameters that are also assigned prior distributions sometimes referred to as hyperpriors. We will not see these until later in the course (Chapter 18).

Derived quantities: these are objects determined using the assignment arrow,

<-. For example, we might be interested in obtaining samples for a function of parameters (e.g.,Age) and modeled parameters (Looping indicies:

Below, we define our model for the jaw data using a function (by contrast, Kéry (2010) and others often write the model out to a file).

jaw.mod<-function(){

# Priors

mu.male ~ dnorm(100, 0.001) # mean of male jaw lengths

mu.female ~ dnorm(100, 0.001) # mean of female jaw lengths

sigma ~ dunif(0, 30) # common sigma

tau <- 1/(sigma*sigma) #precision

# Likelihood (Y | mu.male, mu.female, sigma) = Normal(mu[sex], sigma^2)

for(i in 1:nmales){

males[i] ~ dnorm(mu.male, tau)

}

for(i in 1:nfemales){

females[i] ~ dnorm(mu.female, tau)

}

# Derived quantities: difference in means

mu.diff <- mu.male - mu.female

}Here, we can identify the following types of objects in our model:

Modeled data =

males, females(holding our jaw lengths)Unmodeled data =

nmales, nfemalesFixed-effects parameters =

mu.male, mu.female, sigmaRandom-effects parameters (none in this example)

Derived quantities =

tau, mu.diffLooping indexes:

i(used twice)

12.6 Fitting a model using JAGS

We begin by loading the R2jags package as well as the mcmcplots (Curtis 2018), MCMCvis (Youngflesh 2018), and ggplot2 (Wickham 2016) packages to help with visualizing the results.

library(R2jags)

library(mcmcplots)

library(MCMCvis) To begin sampling, JAGS will need a set of initial values (our

The function, init.vals, below can be used to generate initial values:

# Function to generate initial values

init.vals<-function(){

mu.male <- rnorm(1, 100, 100)

mu.female <- rnorm(1, 100, 100)

sigma <- runif(1, 0, 10)

out <- list(mu.male = mu.male, mu.female = mu.female, sigma = sigma)

}We will also create objects to hold some of the unmodeled data that we will pass to JAGS, namely the number of males and females in the data set.

#' Create rest of the data for the model

nmales<-length(males)

nfemales<-length(females)We then use the jags function to call JAGS and generate our MCMC sample:

t.test.jags <- jags(data=c("males", "females", "nmales", "nfemales"),

inits = init.vals,

parameters.to.save = c("mu.male", "mu.female", "sigma", "mu.diff"),

progress.bar = "none",

n.iter = 10000,

n.burnin = 5000,

model.file = jaw.mod,

n.thin = 1,

n.chains = 3)Note the following arguments:

datawill contain all modeled and unmodeled data (here,malesandfemalescontaining the jaw lengths andnmalesandnfemalescontaining the number of males and females).parameters.to.saveis a list of parameters for which we want to save the MCMC samples. Here, we specify that we want to keep track ofprogress.bar = "none"(for Windows users, you can also try progress.bar =gui). If we don’t supply this argument, you will get a lot of output in your html file when using Rmarkdown.n.iter = 10000specifies the total number of samples we want to generaten.burnin = 5000specifies that we want to throw away the first 5000 samplesmodel.file = jaw.modspecifies the function containing the model specificationn.thin = 1specifies that we want to keep all of the samples. We can save memory by saving say every other sample if we change this ton.thin = 2. If the chains are highly autocorrelated, we won’t lose much information by keeping every other sample.n.chains = 3specifies that we want to generate 3 Markov chains, each generated with a different set of starting values.

Alternatively, we could use jags.parallel to take advantage of parallel processing using:

t.test.jags <- jags.parallel(data = c("males", "females", "nmales", "nfemales"),

inits = init.vals,

parameters.to.save = c("mu.male", "mu.female", "sigma", "mu.diff"),

n.iter = 10000,

n.burnin = 5000,

model.file = jaw.mod,

n.thin = 1,

n.chains = 3)Let’s inspect the output from jags by typing t.test.jags (the name of the object we created).

t.test.jagsInference for Bugs model at "jaw.mod", fit using jags,

3 chains, each with 10000 iterations (first 5000 discarded)

n.sims = 15000 iterations saved. Running time = secs

mu.vect sd.vect 2.5% 25% 50% 75% 97.5% Rhat n.eff

mu.diff 4.779 1.508 1.775 3.797 4.772 5.760 7.740 1.001 15000

mu.female 108.602 1.064 106.501 107.912 108.598 109.284 110.683 1.001 15000

mu.male 113.381 1.069 111.262 112.688 113.375 114.082 115.511 1.001 9600

sigma 3.317 0.594 2.380 2.895 3.239 3.655 4.701 1.002 3200

deviance 103.075 2.744 99.892 101.036 102.395 104.379 110.156 1.001 4900

For each parameter, n.eff is a crude measure of effective sample size,

and Rhat is the potential scale reduction factor (at convergence, Rhat=1).

DIC info (using the rule: pV = var(deviance)/2)

pV = 3.8 and DIC = 106.8

DIC is an estimate of expected predictive error (lower deviance is better).We see that we get a summary of the posterior distribution for each saved parameter:

mu.vect= the mean of the posterior distributionsd.vect= the standard deviation of the posterior distribution2.5%to97.5%= quantiles of posterior distributionRhatis the Gelman-Rubin statistic for evaluating convergence of the MCMC samples.n.eff= an estimate of the effective sample size. As we will see in a bit, our MCMC samples will typically be autocorrelated. Thus, they will contain less information than if we were able to somehow generate a set of independent samples from the posterior distribution.

JAGS also returns an estimate of DIC (an information theoretic quantity like AIC that we will briefly discuss in Section 15.8.4).

If we only wanted to view the output for a few select parameters, we can use the MCMCsummary function in the MCMCvis package (Youngflesh 2018):

MCMCsummary(t.test.jags, params = c("mu.male", "mu.female")) mean sd 2.5% 50% 97.5% Rhat n.eff

mu.male 113.3814 1.069292 111.2623 113.3752 115.5112 1 15000

mu.female 108.6021 1.064330 106.5008 108.5981 110.6833 1 15364Before interpreting the output, we should verify that we have sampled long enough that our samples have converged in distribution. Inspecting the values of Rhat, we see that they are all close to 1. It is also a good idea to inspect posterior density plots and trace plots to provide further reassurance that the different chains have ended up in the same spot (see Section 12.7).

We can use the MCMCpstr function in the MCMCvis package to pull off the posterior means to serve as our point estimates and to pull off quantiles of the posterior distribution to form 95% credible intervals.

# Use MCMCsummary to pull off posterior means

bayesests <- MCMCpstr(t.test.jags, params = c("mu.male", "mu.female"), func = mean)

bayesests$mu.male

[1] 113.3814

$mu.female

[1] 108.6021# Use MCMCsummary to pull of upper and lower 95% credible interval limits

bayesci <- MCMCpstr(t.test.jags, params = c("mu.male", "mu.female"),

func = function(x) quantile(x, probs = c(0.025, 0.975)))

bayesci$mu.male

2.5% 97.5%

mu.male 111.2623 115.5112

$mu.female

2.5% 97.5%

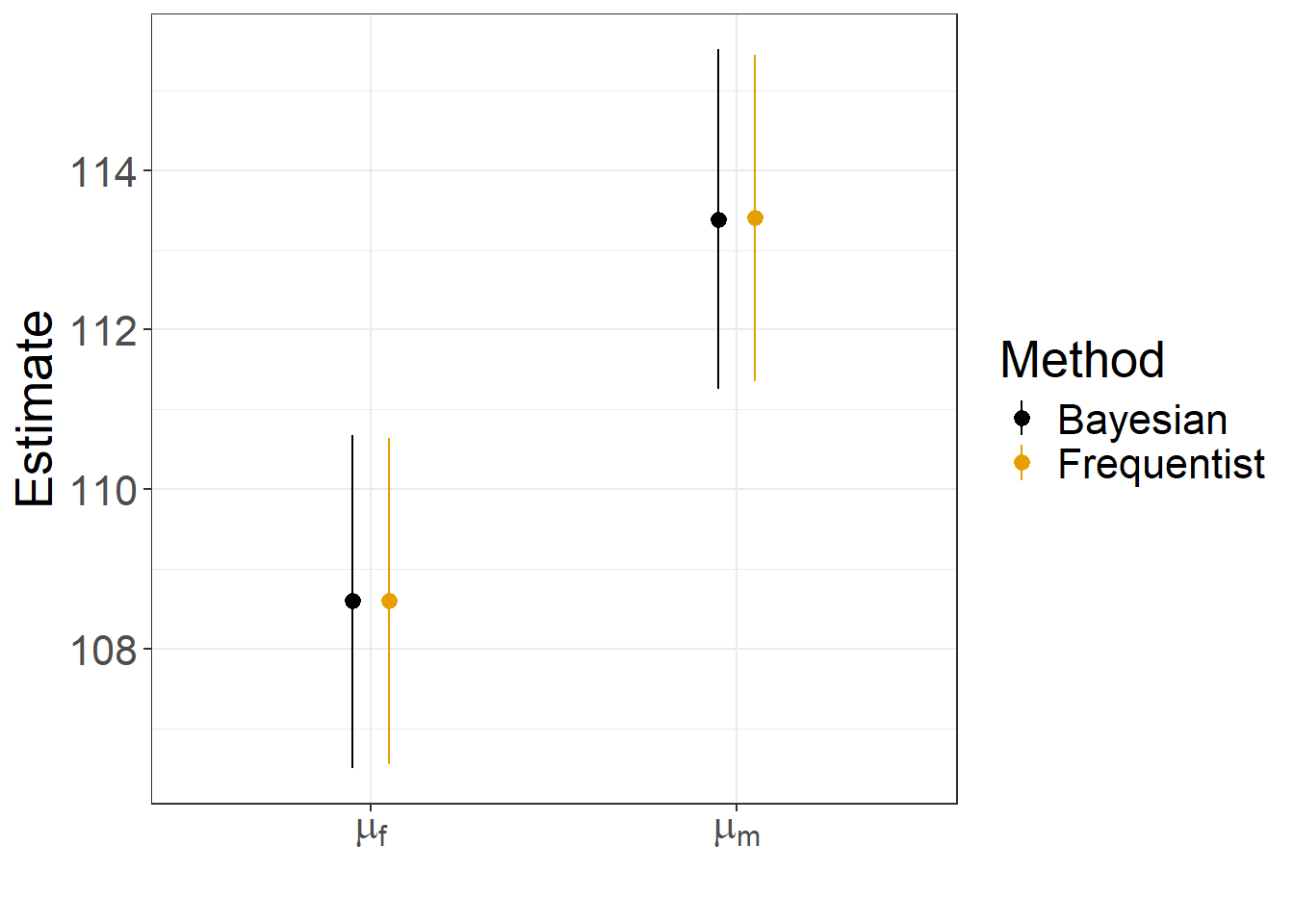

mu.female 106.5008 110.6833We then fit the same model in a frequentist framework using lm and create a data set with our estimates and credible/confidence intervals.

# Fit linear model in frequentist framework

jawdat<-data.frame(jaws=c(males, females),

sex=c(rep("Male", length(males)),

rep("Female", length(females))))

lm.jaw<-lm(jaws~sex-1, data=jawdat)

# Store results

betaf <- coef(lm.jaw)

CIf <-confint(lm.jaw)

ests<-data.frame(estimate = c(bayesests$mu.female, bayesests$mu.male, betaf),

LCL = c(bayesci$mu.female[1], bayesci$mu.male[1], CIf[,1]),

UCL = c(bayesci$mu.female[2], bayesci$mu.male[2], CIf[,2]),

param = c("Mean females", "Mean males"),

Method = rep(c("Bayesian", "Frequentist"), each = 2))Lastly, we plot the results, showing that they are nearly identical (Figure 12.3)!

ggplot(ests, aes(param,estimate, col = Method)) +

geom_point(position = position_dodge(width = 0.2))+

geom_pointrange(aes(ymin = LCL, ymax= UCL), position = position_dodge(width = 0.2))+

ylab("Estimate") + xlab("") +

scale_x_discrete(labels = c('Mean females' = expression(mu[f]),

'Mean males' = expression(mu[m]))) +

scale_colour_colorblind()+

theme(text = element_text(size = 20)) 12.7 Density and traceplots for assessing convergence

When running code in Rstudio, I often like to use the mcmcplot function to visualize output. This function will create a separate html file that you can use to visualize posterior distributions, autocorrelation functions, and traceplots for the different parameters. This function does not work well with the bookdown package Xie (2022) used to create this book, however, so we will explore these different plots separately.

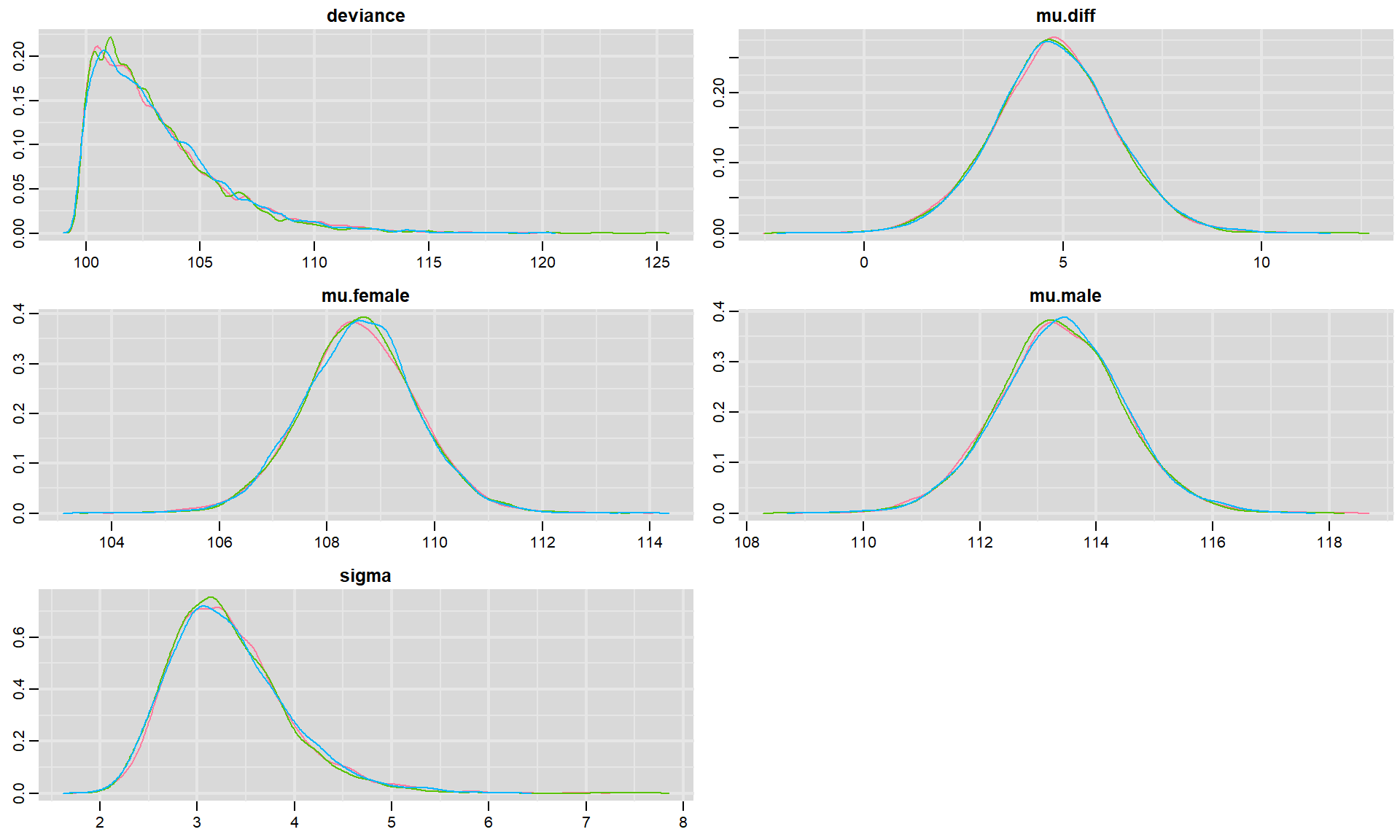

We can visualize posterior densities using denplot:

denplot(t.test.jags, ask = FALSE) In each panel, we see density plots for each chain associated with a particular parameter as well as density plots for the deviance (we can also pool results across the different chains if we add collapse = TRUE). For this simple model, it is clear that all three chains ended up in the same place, providing further evidence that we have reached convergence. If we had a large number of parameters, then we could have added the parms argument to provide a list containing a subset of parameters to visualize. For example, we could visualize the posteriors for denplot(t.test.jags, parms = c("mu.male", "mu.female"))1.

We can also look at traceplots showing the sequence of posterior samples using:

traplot(t.test.jags, ask=FALSE)Again, the fact that the different chains largely overlap is reassuring. Sometimes, traceplots will not look so noisy - but, rather you will see a slow moving trend over time. When this happens, the samples are highly autocorrelated, and we will have to sample for a long time in order to explore the full range of the posterior distribution. By contrast, these traceplots suggest that the sample is doing a great job quickly exploring the full range of the posterior distribution, and we say the chains are “well mixed”.

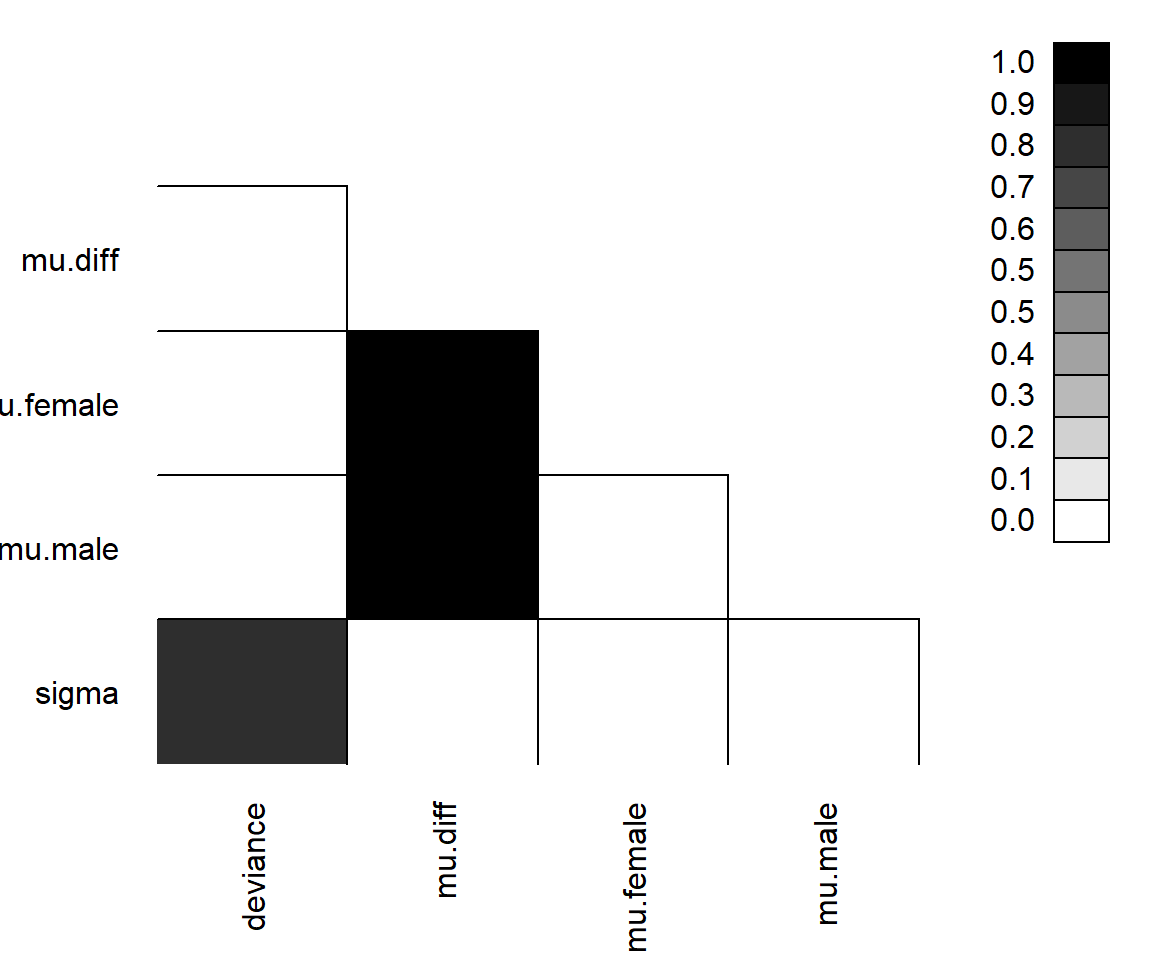

We can look to see if our parameters are correlated with each other using parcorplot.

parcorplot(t.test.jags)

parcorplot function for inspecting whether the posterior distributions are correlated for different parameters (Figure 12.6).

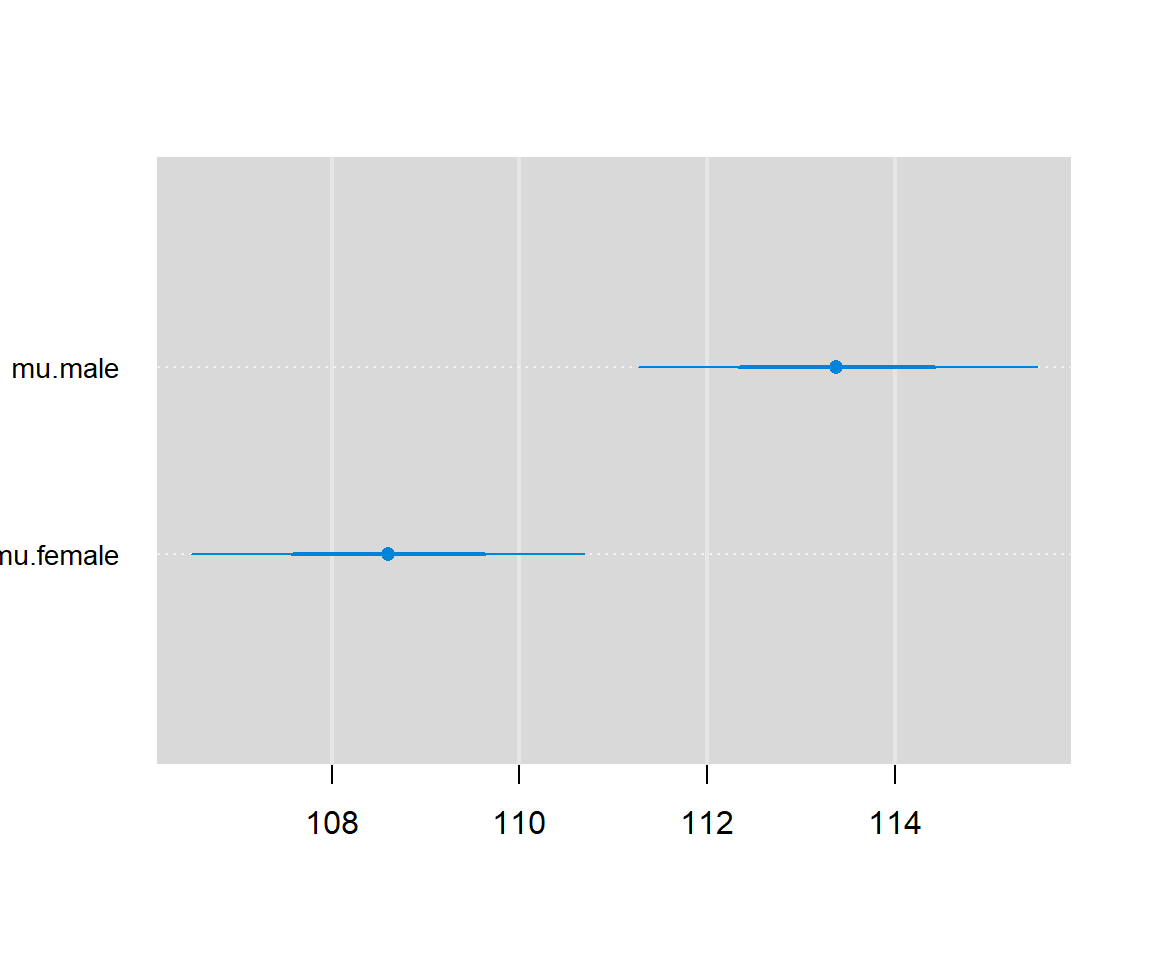

Lastly, we can plot estimates with 68% and 95% credible intervals using the caterplot function (Figure 12.7)2.

caterplot(t.test.jags, ask = FALSE,

parms = c("mu.male", "mu.female"))

caterplot function applied to the Bayesian model fit to the jaw length data.

Congrats - you have just fit your first JAGS model and learned how to work with and summarize samples from the posterior distribution!

12.8 Tips on running models in JAGS

Kéry (2010) offers lots of good tricks and tips in the Appendix of his book. First and foremost: start simple, then build up towards more complex models! If you have his book, we encourage you to look at his tips numbered: 2, 3, 4, 9, 11, 12 (use %T% in JAGS), 14, 16, 17, 20, 23,24, 25, 26, 27.

Also, as always, googling error messages can be useful for diagnosing problems, and it can help to work together with your peers when first learning to program in JAGS. It is extremely rare to specify everything correctly the first time when fitting a model using JAGS. That is OK. It is important to have failures followed by successes to give future you the confidence needed to stick with it!

12.9 References

Note, the functions in the

mcmcplotspackage include the argumentparms, whereas the functions in theMCMCvispackage include the argumentparams. It is easy to get these confused. If you use the tab key in Rstudio after typing “par”, you can have the function self-populate with the correct argument.↩︎Note, for a Normal distribution, a 68% interval is given by